Background

Untreated age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of vision loss in people 55 years of age and older in developed countries. Millions of Americans have the intermediate form of AMD, putting them at risk of developing advanced AMD, which can lead to legal blindness in some cases.

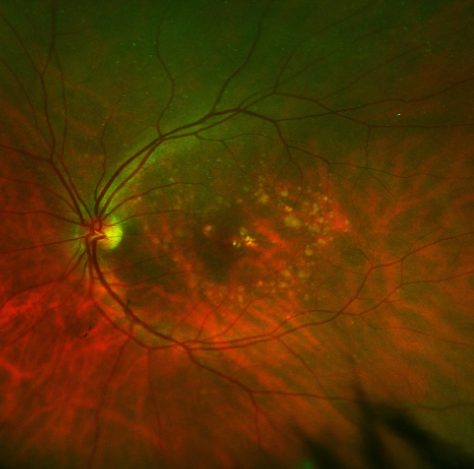

The two types of macular degeneration are nonneovascular (the “dry” form) and neovascular (the “wet” form). Patients with dry macular degeneration have age related changes to their retina including drusen and/or color changes to their retina.

Dry macular degeneration with numerous drusen in the macula.

Patients with advanced dry AMD can develop geographic atrophy, with resulting central loss of vision called a scotoma. This can result in a central blind spot in the vision. Dry AMD may progress to wet AMD. Wet AMD is characterized by choroidal neovascular membranes (CNV), which can grow under the retina. Untreated wet AMD can lead to formation of scar tissue that causes irreversible visual loss.

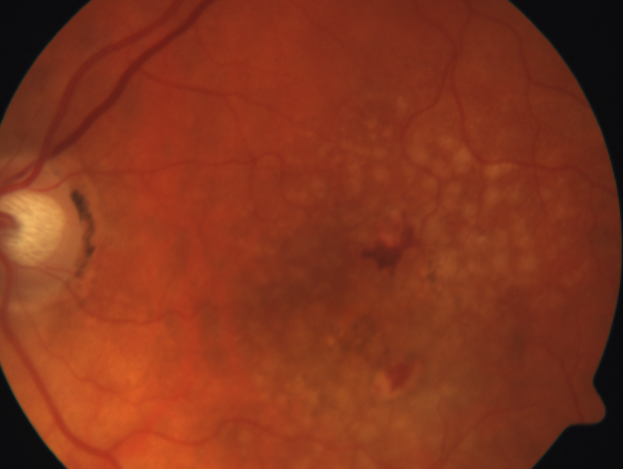

New bleeding can occur as dry macular degeneration transforms into wet macular degeneration.

If individuals progress from dry to wet AMD, treatment with intravitreal injections of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors is effective in reducing the risk of severe vision loss. Treatment can improve vision in some patients. To date, there is no effective treatment to halt the progression of geographic atrophy from dry AMD, although it is the object of current research.

Treated wet macular degeneration with have atrophic areas and scar tissue formation.

Diagnosis

Clinical Exam

Patients with new-onset wet AMD typically describe painless, progressive blurring or distortion of their central vision. These symptoms can be acute or insidious in onset. Patients may also complain of central scotomas, which may be noted at home with Amsler grid testing. Clinical examination may demonstrate subretinal fluid, hemorrhage, lipid, or pigment epithelial detachment in the setting of drusen.

Testing

If wet AMD is suspected, optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein angiography may be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. OCT can be used to evaluate the retina in cross-section. In wet AMD, OCT may demonstrate intraretinal or subretinal fluid, retinal thickening, pigment epithelial detachment, and fusiform thickening of the retinal pigment epithelium and Bruch membrane. OCT is especially useful for analyzing treatment responses in neovascular AMD after intravitreal anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections.

Fluorescein angiography may demonstrate leakage in a pattern consistent with CNV. Fluorescein angiography is primarily used for initial diagnosis to rule out masquerading conditions. In addition, repeat fluorescein angiography imaging may be helpful, when following eyes that have a suboptimal response to current therapy, in investigating how the choroidal neovascular lesion has changed.

Management

Prevention with Vitamins

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) was a multicenter, randomized phase 3 study building on the earlier AREDS study, which established the role of antioxidants for prevention of advanced AMD. The AREDS2 trial evaluated the effectiveness of adding lutein and zeaxanthin to the original micronutrient supplementation. Based on the AREDS2 results, the current recommendation includes vitamin supplementation with 500 mg vitamin C, 400 IU vitamin E, 10 mg of lutein, 2 mg of zeaxanthin, 80 mg of zinc, and 2 mg of copper for patients with intermediate or advanced AMD.

Laser Photocoagulation

The Macular Photocoagulation Study report provided evidence that intervention with laser photocoagulation was better than observation alone; however, this therapy was suboptimal due to the immediate damage to the overlying neurosensory retina, as well as the high rate (50%) of recurrent CNV. Laser photocoagulation is no longer a good option for the treatment most people with CNV. The procedure still may be an option for small, well-demarcated extrafoveal lesions. However, close follow-up for recurrent CNV is necessary.

Photodynamic Therapy

The approval of photodynamic therapy in the year 2000 offered an alternative to thermal laser photocoagulation. The Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration with Photodynamic Therapy (TAP) and Verteporfin in Photodynamic Therapy (VIP) trials showed that photodynamic therapy was effective in slowing the rate of vision loss, although it was not beneficial in all lesion types and was not associated with significant visual acuity gain. Currently, photodynamic therapy is not widely used to treat CNV. Typically, it is reserved for use in combination with intravitreal anti-VEGF agents for CNV associated with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy or when disease is refractory to anti-VEGF agents.

Intravitreal Anti–Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Inhibitors

The advent of pharmacologic agents that specifically target angiogenesis, such as those directed against VEGF, hailed a new era in the management of neovascular AMD. VEGF spurs the growth of abnormal blood vessels and causes increased vascular permeability. The gold standard of treatment of most forms of wet AMD is now intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF medication.

Treatment Strategies

The most thoroughly tested treatment strategy by clinical trials is the monthly dosing strategy, where a patient receives an injection every month in the affected eye. Another proven strategy is “as needed” treatment based on clinical exam findings. However, the most common dosing strategy in current clinical practice is called “treat and extend,” in which patients are given a treatment at every visit, and the time between visits is lengthened if there is no sign of disease activity.

Conclusion

Treatment with intravitreal anti-VEGF agents (aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab) is the current preferred treatment for wet AMD. Anti-VEGF therapy can be dosed monthly, as-needed, or using the treat-and-extend strategy. All 3 anti-VEGF agents are effective in treating CNV and improving vision. In addition, these agents have been shown to be safe for patients. Your doctor will help you decide which treatment is best for you.